Looking ahead to the year 2026, patriotic Americans of every persuasion wonder how to use a complicated occasion with a difficult name (semiquincentennial? Really?) to promote renewed pride, gratitude and a fresh sense of national unity.

To make the most of the upcoming observance of the 250th anniversary of the nation’s independence, analysts and activists frequently look back to grand celebrations of the past, such as Philadelphia’s glorious Centennial of 1876, or the fondly remembered, national Bicentennial of 1976, but they generally ignore the more relevant if less memorable festivities of 100 years ago next summer.

The heavily-hyped Sesquicentennial of 1926, marking the first one hundred and fifty years of the Republic’s existence, gets much less attention for an obvious reason: in the eyes of its own financially battered promoters and much of the skeptical public, it turned out to be an embarrassing disappointment. As far away as Hollywood, Variety, even then the self-proclaimed “Bible” of the entertainment industry, proclaimed the Sesquicentennial to be “America’s Greatest Flop.” The year after this second World’s Fair in Philly (1927) finished its troubled run, the sponsoring organization went into receivership and its tarnished assets were sold off at auction.

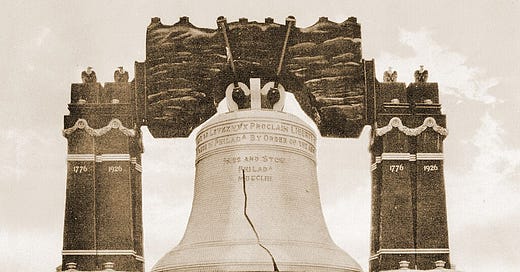

This ignominious fate may well have included the fair’s monumental symbol—a gigantic replica of the Liberty Bell, rising more than 80 feet (eight stories) from the ground and illuminated by 26,000 electric bulbs to correspond to the year of the celebration in 1926.

The initial concept for this ambitious, new observance of the Declaration of Independence came from John Wanamaker, owner of Wanamaker’s department stores and the sole survivor of the group of financiers who had enjoyed great success fifty years earlier with the Centennial Exposition of 1876. That gathering generated worldwide excitement with its introduction of amazing new inventions like the sewing machine, the typewriter and, most significantly, the telephone. It also benefited from a magnificent location: Philadelphia’s spectacularly verdant Fairmount Park, which, with 2,050 acres, offered nearly three times the space of New York’s Central Park and occupied both sides of the scenic Schuylkill River. The buildings, which dazzled more than 10,000,000 visitors from every part of the world, aimed for epic and ornate grandeur to highlight America’s near-miraculous resurgence and reunification after the sweeping destruction and slaughter of the Civil War.

The Sesquicentennial, by contrast, struck many observers as tacky, temporary and more reminiscent of a state fair than a classic and sweeping tribute to international cooperation and achievement. The location of the new fair, in previously undeveloped, marshy territory in South Philadelphia, near the Navy Yard, hardly helped. This large tract happened to be the property of the Republican boss of Philadelphia at the time, William Vare, who profited handsomely from the siting of the new venture.

One of its principal structures, horse-shoe shaped Municipal Stadium (later renamed JFK Stadium), hosted regular performances of a “Patriotic Pageant” called “Freedom,” attempting (feebly) to replicate lavish Broadway productions. The stadium also staged a famous prize fight between world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and challenger Gene Tunney. The popular champ lost, while the record crowd of 130,000 lasted for 10 rounds in the pouring rain.

Weather, in fact, became a major problem for the Sesquicentennial World’s Fair, with storms dampening spirits (and attendance) for its opening days in May, and discouraging customers for 107 of the 184 days that the exposition opened to the public before closure in November. Throughout the summer and Fall, attendance figures proved so weak that only 4,622,211 paid to visit the fair—less than half of the participation at the previous Centennial Exposition fifty years earlier.

Some analysts defend the manifold mistakes of the event’s planners, suggesting that the mass availability of movies and automobiles made world fairs less appealing to the public, wherever or however they happened to be staged. But the unalloyed success and popularity of the great New York gathering of 1939 and other subsequent triumphs give the lie to the argument.

Concerning Philly’s failure in 1926, the example of one ambitious attraction should help guide efforts to plan more meaningful festivities in 2026. “Colonial High Street” involved a slap-dash and unconvincing replication of a Philadelphia neighborhood of the Revolutionary period, complete with actors dressed in costumes and powder whigs of the era, interacting with tourists—who could have seen scores of real colonial structures that had survived in Philadelphia’s Center City just a few miles away.

In fact, the enduring popularity of Independence Hall and other historical sites for those who seek a more intimate understanding of the founders should provide a reminder to those planning for next year’s Semiquincentennial. They should remember the advantages of the real Liberty Bell over the eight-story, behemoth alternative with its 26,000 lights, which once marked the entrance to the failed fair. When it comes to connecting with the incomparable architects of this uniquely favored land, authenticity always matters more than glitz or monumentality.