Ben (Franklin), Amos the Mouse, and Me

During my preschool years, a Disney mouse changed my life—and no, it wasn’t Mickey.

The inspirational rodent who captured my five-year-old imagination was, rather Amos Mouse, co-star of the marvelous, twenty-minute animated classic, Ben and Me. Based on a celebrated children’s book by Robert Lawson, the film version won an Oscar nomination for Best Short Subject in 1953.

Lawson, as writer and illustrator, specialized in stories about famous figures (Christopher Columbus, Paul Revere, and the real-life pirate, Captain Kidd) as told from the point of view of a companion animal. The most successful of these man/beast partnerships first appeared in book form in 1939 (the same epic movie year as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Gone with the Wind) bearing the ponderous title: Ben and Me: An Astonishing Life of Benjamin Franklin by His Good Mouse Amos. Lawson tried to provide his young readers with a far more complete version of Franklin’s remarkable life than Disney did in the brief but magical animated adaptation.

To cover some of the Founding Father’s history-making achievements within the film’s less than half-hour span, the cartoon Ben invents both the Franklin Stove and bifocal spectacles on the same wintry night in 1745, and in both cases Amos Mouse jauntily provides the real technological breakthroughs. He also rides a passenger box in the kite that Franklin famously flies in order to establish the connection between lightening and electricity—though the storm portrayed with frightening intensity takes a painful toll on the unsuspecting Amos.

Most noteworthy of all these quick and often amusing episodes, is the collaboration between Ben, Thomas Jefferson and Amos in overcoming their frustrations in the summer of ’76 to complete the text of the Declaration of Independence. Franklin and Ben did in fact participate in the committee of five assigned to prepare that historic document, but there’s no hint in the primary sources that a tiny creature with a long tail, cocked hat and avid taste for cheese played any significant role. Yet the cartoon classic does suggest that the famous opening of the nation’s founding document (“When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people, to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another…”) originally applied to Ben and Amos, as the mouse insisted on his own independence as the price of preserving his long-time friendship with the printer and patriot.

Watching this small but unforgettable film today, it’s easy to recall and even to understand my fervent fascination all those many years ago. My mother, who took me to see the cartoon in a movie theatre (no streaming, or DVD, or even VHS available in those days) made it clear that Amos Mouse never actually aided the real heroes of history. But it seemed to me, even at an early age, an encouraging notion that such a Titan of his times might have opened a special door in his eighteenth-century head gear to accommodate his endearingly unobtrusive partner for ride-alongs as they walked the streets of colonial Philadelphia.

And the city of my birth (but not Franklin’s—he had begun life’s journey in Boston) also played a real role in my connection to the film. The Liberty Bell appears on screen, and my father had taken me to see that famous relic, just outside Independence Hall, which also makes a cameo appearance in the movie. I felt proud to tour the same sites that both Ben and Tom, if not Amos, had actually consecrated in passing. The monumental statue of Franklin, depicted on screen at the opening of the cartoon, reminded me then of the gigantic memorial at the Franklin Institute—the science museum that my parents also shared with me before I could really absorb anything of the actual contributions celebrated in its halls.

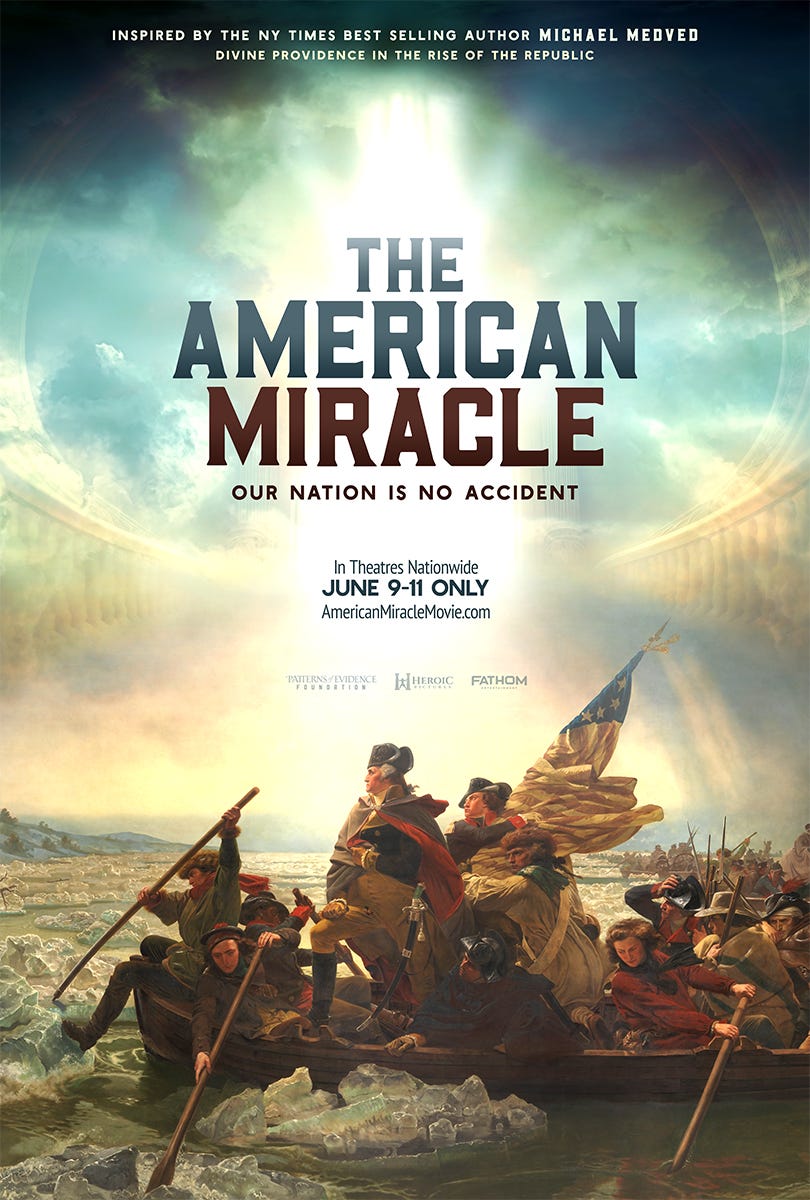

It would be overstating my case to suggest that these ancient recollections led directly to my abiding adult interest in Colonial and Revolutionary America, but it’s also unnecessary to ignore the role of those childhood experiences as background for the new movie, The American Miracle, based on my own book of the same title. Of course, the real Benjamin Franklin, a polymath of staggering intellect and immeasurable impact, is only tangentially related to the stumbling, bumbling mostly comic figure that the Disney animators offered to the post-war public.

Yes, I assume that the real founders, including Franklin and Jefferson (and Washington and Adams) who appear on the pages of my book and the scenes of our movie (opening nationwide on a thousand screens on June 9), will get a more complete and respectful treatment than anything in a popular short subject designed for the kiddies of two generations ago.

But Ben and Me, to very young viewers (like me) at the time, made the nation’s founders seem more accessible, and sympathetic than the grandiose, marbleized figures depicted in statuary and, later, text books. As we approach next year’s celebration of the Republic’s 250th anniversary, it’s appropriate to feel connected to the giants of the past as highly individualistic family members, intimate acquaintances whose astonishing achievements do suggest an air of fairy tale enchantment, even without the participation of a gifted but underappreciated patriotic mouse.