The first political debate I can remember occurred in my nursery school class as part of the election campaign of 1952 and centered on the issue of the relative ages of the two candidates for the presidency.

Before I had reached the age of four, I possessed limited understanding of the deeper distinctions in the contest between General Dwight Eisenhower and his Democratic opponent Adlai Stevenson. My only real perspective on the race involved the fact that my parents favored Stevenson, while my best friend, Ricky, came from a family that enthusiastically backed the World War II general who represented the Republicans. But as election day approached, Ricky made a devastating point that forced me to concede that his champion, General Ike, boasted a substantive advantage over my family’s inferior favorite. “He’s older,” Ricky authoritatively observed. “That means he’s smarter, right?”

Crushed by this confrontation, I immediately went to our nursery school teacher, Mrs. O’Neill, to confirm or deny the essence of my opponent’s argument. Sure enough, he had reported accurately on Ike’s age advantage: the history books show Eisenhower as 62 when he ran for his first term, while Stevenson had barely reached his fifty-second birthday. It never occurred to me as an aspiring preschool pundit to question the notion that a more advanced age equated to superior intelligence, virtue and understanding.

Today we seem to operate under the opposite assumption: the fact that Joe Biden registers as nearly four years older than Donald Trump seems to make him far more vulnerable to suspicions of senility and muddled memory than his slightly more youthful rival, and fails to confer advantages of any kind. Of course, part of this reaction stems from the President's occasionally unfocused demeanor and garbled pronouncements which have, regardless of his age, represented an element of his persona for at least the last four decades.

To come to terms with the age issue in our present politics, it’s worth considering its complicated history over the last 200 years, which began with one mostly-forgotten candidate who, as it turned out, was indeed too aged and infirm to serve successfully as president.

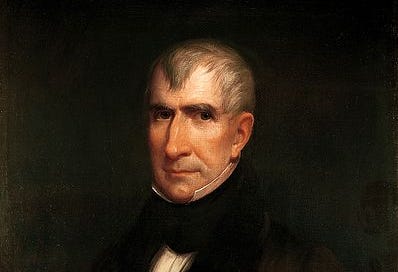

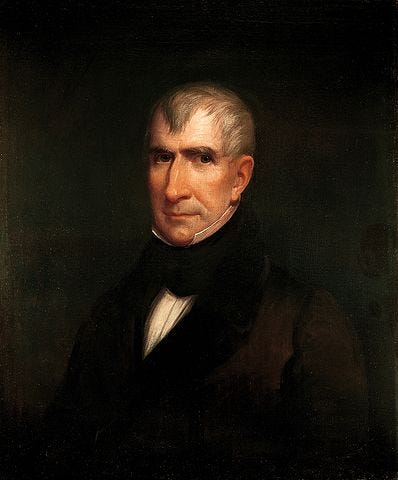

William Henry Harrison ran unsuccessfully for the White House in 1836, but four years later the aging war hero succeeded in winning the presidential nomination of the Whig Party. This made him, at age 67, the oldest American at that point ever chosen by a major party as its standard bearer. During the resulting campaign of 1840, his Democratic opponents derided him as “Granny Harrison, the Petticoat General”, citing his advanced age and his controversial, long-ago resignation from the military while the War of 1812 still raged. Harrison nevertheless emphasized his most celebrated battlefield achievement, the victory against the Indian insurgent Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe. That triumph had occurred a full thirty years earlier, but nonetheless enabled “Old Tippecanoe” to win in a landslide against the younger incumbent, Martin van Buren.

As he approached his inauguration, Harrison felt fiercely determined to display the manly vigor associated with his past and to overcome the remaining skepticism about his advanced age. He did so by delivering by far the longest inaugural address in the nation’s history—8,445 words and requiring nearly two hours in the new president’s impassioned reading. He accomplished this feat on a wet and bitterly cold day, with no overcoat or hat, but immediately thereafter contracted the illness (possibly pneumonia) that killed him only one month into his presidency.

After this dramatic disaster, the American people for more than a century avoided candidates who would have been even older than Harrison. In 1872, a losing contender provided a powerful reminder of the dangers of poor health and infirmity even for a world-famous celebrity who seemed full of life and vigor at age 61. Newspaper titan Horace Greeley accepted the presidential nominations of both the Democrats and the newly organized Liberal Republicans to challenge President Grant’s bid for a second term. Greeley would have been an underdog in any event, but in October of the election year he suspended his aggressive campaign because of his wife’s grave, and ultimately fatal, illness. Greeley himself died after losing the election, but before the Electoral College had cast its ballots—leaving the awkward challenge of how to count electors whose votes have been pledged to a candidate who is already deceased.

Illness and infirmity also played a role in the presidencies of prominent twentieth-century leaders including Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan, but in each of these cases their heroic stature in the eyes of their admirers encouraged the idea (disastrously wrong in the case of Wilson and FDR) that the admired champion could surmount any of the challenges of advancing age.

Reagan’s situation in the early months of his first term registered as especially dramatic: inaugurated in 1981, just days before his 70th birthday. His Hollywood glamor and well-advertised active lifestyle prevented hostile focus on his status as the most elderly of our newly installed presidents up to that time. Then two months later came an assassination attempt with the new chief executive gallantly, and some would say, miraculously, surviving a bullet to the chest. When running for a second term, media commentary raised questions about his occasional incoherence and fumbling but the incumbent responded with a perfectly timed and devastatingly effective joke near the end of his second televised debate.

“I want you to know that also I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience,” he declared, in a riposte for the ages, and for the aged. The age issue made so little impact in 1984 that Reagan, in his mid-seventies, carried 49 of 50 states.

Reagan’s famous line worked as well as it did because no successful candidate has ever actually used the age issue in the other direction—damaging an opponent for his youth and inexperience. Among the presidential contenders who ran for the top job while still below the age of 50 and won attention for their youthfulness—James Garfield, William Jennings Bryan, John F. Kennedy, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama—most of them had already compiled extensive political experience (Clinton served 12 years as governor of Arkansas). The others (Bryan, who counted at age 36 as the first populist to seize the Democratic nomination, or Obama, as the first nominee of color) enjoyed historic status that supported their candidacy as ground-breaking outsiders.

In any event, except for nursery school playgrounds in the long-ago fifties, few political analysts have ever considered advanced age an electoral advantage. In the upcoming battle between two contenders who are 81 and 77 respectively, it's hard to imagine that an “age edge” will decisively help either one of them.